The OpenStack Grizzly release of yesterday officially closes the Grizzly

development cycle. But while I try to celebrate and relax, I can't help

from feeling worried and depressed on the hours following the release,

as we discover bugs that we could have (should have ?) caught before

release. It's a kind of postpartum depression for release managers;

please consider this post as part of my therapy.

Good

We'd naturally like to release when the software is "ready", "good", or

"bug-free". Reality is, with software of the complexity of OpenStack,

onto which we constantly add new features, there will always be bugs.

So, rather than releasing when the software is bug-free, we "release"

when waiting more would not really change the quality of the result. We

release when it's time.

In OpenStack, we invest a lot in automated testing, and each proposed

commit goes through an extensive set of unit and integration tests. But

with so many combinations of deployment options, there are still dark

corners that will only be explored by users as they apply the new code

to their specific use case. We encourage users to try new code before

release, by publishing and making noise about milestones, release

candidates... But there will always be a significant number of users who

will not try new code until the point in time we call "release". So

there will always be significant bugs that are discovered (and fixed)

after release day.

The best point in time

What we need to do is pick the right moment to "release": when all known

release-critical issues are fixed. When the benefits of waiting more are

not worth the drawbacks of distracting developers from working on the

next development cycle, or of abandoning the benefits of a predictable

time-based common release.

That's the role of the Release

Candidates that we

produce in the weeks before the release day. When we fixed all known

release-critical bugs, we create an RC. If we find new ones before the

release day, we fix them and regenerate a new release candidate. On

release day, we consider the current release candidates as "final" and

publish them.

The trick, then, is to pick the right length for this feature-frozen

period leading to release, one that gives enough time for each of the

projects in OpenStack to reach this the first release candidate

(meaning, "all known release-critical bugs fixed"), and publish this RC1

to early testers. For Grizzly, it looked like this:

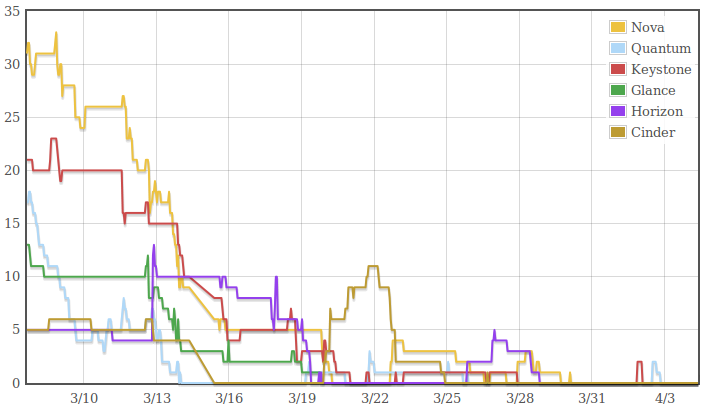

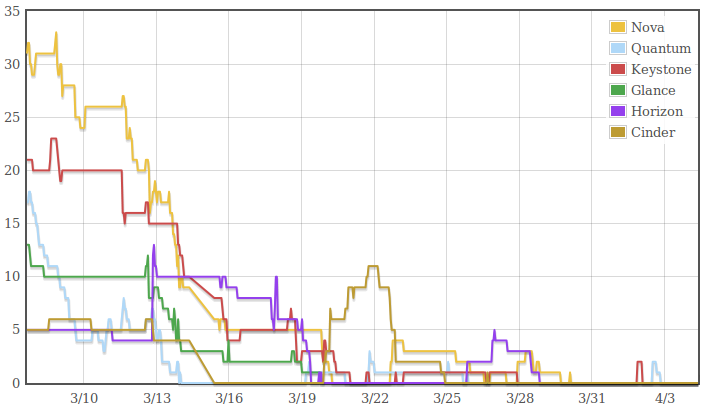

This graph shows the number of release-critical bugs in various projects

over time. We can see that the length of the pre-release period is about

right: waiting more would not have resulted in a lot more bugs to be

fixed. We basically needed to release to get more users to test and

report the next bugs.

The Grizzly is still alive

The other thing we need to have is a process to continue to fix bugs

after the "release". We document the most obvious regressions in the

constantly-updated Release

Notes. And we

handle the Grizzly bugs using the stable release update process.

After release, we maintain a branch where important bugfixes are

backported and from which we'll publish point releases. This

stable/grizzly branch is maintained by the OpenStack stable

maintenance team. If you see a bugfix that should definitely be

backported, you can tag the corresponding bug in Launchpad with the

grizzly-backport-potential tag to bring it to the team's attention.

For more information on the stable branches, I invite you to read this

wiki page.

Being pumped up again

The post-release depression usually lasts a few days, until I realize

that not so many bugs were reported. The quality of the new release is

actually always an order of magnitude better than the previous releases,

due to 6-month worth of improvements in our amazing continuous

integration system ! We actually did an incredible job, and it will only

get better !

The final stage of recovery is when our fantastic community gets all

together at the OpenStack Summit. 4 days to witness and celebrate our

success. 4 days to recharge the motivation batteries, brainstorm and

discuss what we'll do over the next 6 months. We are living awesome

times. See you there.

Back from a (almost) entirely-offline week vacation, a lot of news were

waiting for me. A full

book

was written. OpenStack projects

graduated.

An Ubuntu rolling release

model

was considered. But what grabbed my attention was the announcement of

UDS moving to a virtual

event.

And every 3 months. And over two days. And next week.

As someone who attended all UDSes (but one) since Prague in May 2008, as

a Canonical employee then as an upstream developer, that was quite a

shock. We all have fond memories and anecdotes of stuff that happened

during those Ubuntu developer summits.

What those summits do

For those who never attended one, UDS (and the OpenStack Design

Summits that were modeled after them) achieve a lot of goals for a

community of open source developers:

- Celebrate recent release, motivate all your developer community for

the next 6 months

- Brainstorm early ideas on complex topics, identify key stakeholders

to include in further design discussion

- Present an implementation plan for a proposed feature and get

feedback from the rest of the community before starting to work on

it

- Reduce duplication of effort by getting everyone working on the same

type of issues in the same room and around the same beers for a few

days

- Meet in informal settings people you usually only interact with

online, to get to know them and reduce friction that can build up

after too many heated threads

This all sounds very valuable. So why did Canonical decide to suppress

UDSes as we knew them, while they were arguably part of their successful

community development model ?

Who killed UDS

The reason is that UDS is a very costly event, and it was becoming more

and more useless. A lot of Ubuntu development happens within Canonical

those days, and UDS sessions gradually shifted from being brainstorming

sessions between equal community members to being a formal communication

of upcoming features/plans to gather immediate feedback (point [3]

above). There were not so many brainstorming design sessions anymore

(point [2] above, very difficult to do in a virtual setting), with

design happening more and more behind Canonical

curtains. There is less

need to reduce duplication of effort (point [4] above), with less

non-Canonical people starting to implement new things.

Therefore it makes sense to replace it with a less-costly,

purely-virtual communication exercise that still perfectly fills point

[3], with the added benefits of running it more often (updating everyone

else on status more often), and improving accessibility for remote

participants. If you add to the mix a move to rolling releases, it

almost makes perfect sense. The problem is, they also get rid of points

[1] and [5]. This will result in a even less motivated developer

community, with more tension between Canonical employees and

non-Canonical community members.

I'm not convinced that's the right move. I for one will certainly regret

them. But I think I understand the move in light of Canonical's recent

strategy.

What about OpenStack Design Summits ?

Some people have been asking me if OpenStack should move to a similar

model. My answer is definitely not.

When Rick Clark imported the UDS model from Ubuntu to OpenStack, it was

to fulfill one of the 4 Opens we

pledged: Open Design. In OpenStack Design Summits, we openly debate

how features should be designed, and empower the developers in the room

to make those design decisions. Point [2] above is therefore essential.

In OpenStack we also have a lot of different development groups working

in parallel, and making sure we don't duplicate effort is key to limit

friction and make the best use of our resources. So we can't just pass

on point [4]. With more than 200 different developers authoring changes

every month, the OpenStack development community is way past Dunbar's

number. Thread after

thread, some resentment can build up over time between opposed

developers. Get them to informally talk in person over a coffee or a

beer, and most issues will be settled. Point [5] therefore lets us keep

a healthy developer community. And finally, with about 20k changes

committed per year, OpenStack developers are pretty busy. Having a week

to celebrate and recharge motivation batteries every 6 months doesn't

sound like a bad thing. So we'd like to keep point [1].

So for OpenStack it definitely makes sense to keep our Design Summits

the way they are. Running them as a track within the OpenStack Summit

allows us to fund them, since there is so much momentum around OpenStack

and so many people interested in attending those. We need to keep

improving the remote participation options to include developers that

unfortunately cannot join us. We need to keep doing it in different

locations over the world to foster local participation. But meeting in

person every 6 months is an integral part of our success, and we'll keep

doing it.

Next stop is in Portland, from April 15 to April 18. Join

us !

In 3 weeks, free and open source software developers will converge to

Brussels for 2+ days of talks, discussions and beer.

FOSDEM is still the largest gathering for

our community in Europe, and it will be a pleasure to meet again with

longtime friends. Note that FOSDEM attendance is free as in beer, and

requires no registration.

OpenStack will be present with a number of talks in the Cloud

devroom in the

Chavanne auditorium on Sunday, February 3rd:

There will also be OpenStack mentions in various other talks during the

day: Martyn Taylor should demonstrate OpenStack Horizon in conjunction

with Aeolus Image

Factory at

13:30, and Vangelis Koukis will present

Synnefo, which

provides OpenStack APIs, at 14:00.

Finally, I'll also be giving a talk, directed to Python developers,

about the OpenStack job market sometimes Sunday in the Python

devroom (room

K.3.401): Get a Python job, work on OpenStack.

I hope you will join us in the hopefully-not-dead-frozen-this-time and

beautiful Brussels !

The first milestone of the OpenStack Grizzly development cycle is just

out.

What should you expect from it ? What significant new features were

added ?

The first milestones in our 6-month development

cycles are traditionally not

very featureful. That's because we are just out of the previous release,

and still working heavily on bugs (this milestone packs 399 bugfixes !).

It's been only one month since we had our Design

Summit, so by the time we formalize

its outcome into blueprints and roadmaps, we are just getting started

with feature implementation. Nevertheless, it collects a lot of new

features and bugfixes that landed in our master branches since

mid-September, when we froze features in preparation for the Folsom

release.

Keystone is arguably where the most significant changes landed, with

a tech preview of the new API

version

(v3), with policy and RBAC

access

enabled. A new ActiveDirectory/LDAP identity

backend

was also introduced, while the auth_token middleware is now

shipped

with the Python Keystone client.

In addition to fixing 185

bugs, the Nova crew

removed

nova-volume

code entirely (code was kept in Folsom for compatibility reasons, but

was marked deprecated). Virtualization drivers no longer directly

access the

database, as a

first step towards completely isolating compute nodes from the

database.

Snapshots are now supported on raw and LVM

disks,

in addition to qcow2. On the hypervisors side, the Hyper-V driver grew

ConfigDrive v2

support,

while the XenServer one can now use

BitTorrentas

an image delivery mechanism.

The Glance client is no longer

copied

within Glance server (you can still find it with the Python client

library), and the Glance SimpleDB driver reaches feature

parity

with the SQLAlchemy based one. A number of cleanups were implemented in

Cinder, including in volume drivers code

layout

and API versioning

handling.

Support for XenAPI storage manager for

NFS

is back, while the API grew a call to list bootable

volumes

and a hosts

extension

to allow service status querying.

The Quantum crew was also quite busy. The Ryu plugin was

updated

and now features tunnel

support.

The preparatory work to add advanced

services

was landed, as well as support for highly-available RabbitMQ

queues.

Feature parity gap with nova-network was reduced by the introduction of

a Security Groups

API.

Horizon saw a lot of changes under the hood, including unified

configuration.

It now supports Nova flavor extra

specs.

As a first step towards providing cloud admins with more targeted

information, a system info

panel

was added. Oslo (formerly known as openstack-common) also saw a

number of improvements. The config module (cfg) was ported to

argparse.

Common service management

code

was pushed to the Oslo incubator, as well as a generic policy

engine.

That's only a fraction of what will appear in the final release of

Grizzly, scheduled for April 2013. A lot of work was started in the last

weeks but will only land in the next milestone. To get a glimpse of

what's coming up, you can follow the Grizzly release status

page !

As comparing OpenStack with Linux becomes an increasingly popular

exercise,

it's only natural that people and press articles start to ask where the

Linus Torvalds of OpenStack is, or who the Linus Torvalds of

OpenStack

should be. This assumes that technical leaders could somehow be

appointed in OpenStack. This assumes that the single dictator model is

somehow reproducible or even desirable. And this assumes that the

current technical leadership in OpenStack is somehow lacking. I think

all those three assumptions are wrong.

Like Linux, OpenStack is an Open Innovation project: an independent,

common technical playground that is not owned by a single company and

where contributors form a meritocracy. Assuming you can somehow appoint

leaders in such a setting shows a great ignorance of how those projects

actually work. Leaders in an open innovation project don't derive their

authority from their title. They derive their authority from the respect

that the other contributors have for them. If they lose this respect,

their leadership will be disputed and you'll face the risk of a fork.

Project leaders are not appointed, they are grown. Linus wasn't

appointed, and he didn't decide one day that he should lead Linux. He

grew as the natural leader for this community over time.

Maybe people asking for a Linus of OpenStack like the idea of a single

dictator sitting at the top. But that setup is not easily

reproduced. Three conditions need to be met: you have to be the

founder (or first developer) of the project, your project has to grow

sufficiently slowly so that you can gather the undisputed respect of

incoming new contributors, and you have to keep your hands deep in

technical matters over time (to retain that respect). Linus checked all

those boxes. In OpenStack, there were a number of developers involved in

it from the start, and the project grew really fast, so a group of

leaders emerged, rather than a single undisputed figure.

I'd also argue that the "single leader" model is not really

desirable. OpenStack is not a single project, it's a collection of

projects. It's difficult to find a respected expert in all areas,

especially as we grew by including new projects within the OpenStack

collection. In addition to that, Linux as a project still struggles with

its bus factor of 1 and how

it would survive Linus. Organizing your technical leadership in a way

that makes it easier for leadership to transition to new figures makes a

stronger and more durable community.

Finally, asking for a Linus of OpenStack is somehow implying that the

current technical leadership is insufficient, which is at best ignorant,

at worse insulting. Linus fills two roles within Linux: the technical

lead role (final decision on technical matters, the buck stops here)

and the release management role (coordinating the release development

cycles and producing releases). OpenStack has project technical leads

("PTLs") to fill the first role, and a (separate) release manager to

fill the second. In addition to that, to solve cross-project issues, we

have a Technical

Committee

(which happens to include the PTLs and release manager).

If you are under the impression that this multi-headed technical

leadership might result in non-opiniated choices, think twice. The new

governance model establishing the Technical Committee and the full

authority of it over all technical matters in OpenStack is only a month

old, previously the project (and its governance model) was still owned

by a single company. The PTLs and Technical Committee members are highly

independent and have the interests of the OpenStack project as their top

priority. Most of them actually changed employers over the last year and

continued to work on the project.

I think what the press and the pundits actually want is a more visible

public figure, that would make stronger design choices, if possible with

nice punch lines that would make good

quotes. It's true that the

explosive growth of the project did not leave a lot of time so far for

technical leaders of OpenStack to engage with the press. It's true that

the OpenStack leadership tends to use friendly words and prefer

consensus where possible, which may not result in memorable quotes. But

confusing that with weakness is really a mistake. Technical leadership

in OpenStack is just fine the way it is, thank you for asking.