OpenStack development is organized around a mission, a

governance model

and a set of principles.

Project teams apply for inclusion, and the

Technical Committee (TC),

elected by all OpenStack contributors, judges whether that team work helps

with the OpenStack mission and follows the OpenStack development principles.

If it does, the team is considered part of the OpenStack development

community, and its work is considered an official OpenStack project.

The main effect of being official is that it places the team work under the

oversight of the Technical Committee. In exchange, recent contributors to that

team are considered

Active Technical Contributors

(ATCs), which means they can participate in the vote to elect the Technical

Committee.

Why ?

When you want to create a new official OpenStack project, the first thing to

check is whether you're doing it for the right reasons. In particular, there

is no need to be an official OpenStack project to benefit from our outstanding

project infrastructure (git repositories, Gerrit code reviews, cloud-powered

testing and gating). There is also no need to place your project under the

OpenStack Technical Committee oversight to be allowed to work on something

related to OpenStack. And the ATC status no longer brings additional benefits,

beyond the TC election voting rights.

From a development infrastructure standpoint, OpenStack provides the

governance, the systems and the neutral asset lock to create open

collaboration grounds. On those grounds multiple organizations and

individuals can cooperate on a level playing field, without one

organization in particular owning a given project.

So if you are not interested in having new organizations contribute to your

project, or would prefer to retain full control over it, it probably makes

sense to not ask to become an official OpenStack project. Same if you

want to follow slightly-different principles, or want to relax certain

community rules, or generally would like to behave a lot differently than other

OpenStack projects.

What ?

Still with me ? So... What would be a good project team to propose for

inclusion ? The most important aspect is that the topic you're working on

must help further the OpenStack Mission, which is to produce a ubiquitous

Open Source Cloud Computing platform that is easy to use, simple to implement,

interoperable between deployments, works well at all scales, and meets the

needs of users and operators of both public and private clouds.

It is also very important that the team seamlessly merges into the OpenStack

Community. It must adhere to the

4 Opens

and follow the OpenStack

principles.

The Technical Committee made a number of choices to avoid fragmenting the

community into several distinct silos. All projects use Gerrit to propose

changes, IRC to communicate, a set of

approved programming languages...

Those rules are not set in stone, but we are unlikely to change them just

to facilitate the addition of one given new project team. All those

requirements are summarized in the

new project requirements

document.

The new team must also know its way around our various systems, development

tools and processes. Ideally the team would be formed from existing OpenStack

community members; if not the

Project Team Guide

is there to help you getting up to speed.

Where ?

OK, you're now ready to make the plunge. One question you may ask yourself

is whether you should contribute your project to an existing project team,

or ask to become a new official project team.

Since the recent

project structure reform

(a.k.a. the "big tent"), work in OpenStack is organized around groups of

people, rather than the general topic of your work. So you don't have to ask

the Neutron team to adopt your project just because it is about networking.

The real question is more... is it the same team working on both

projects ? Does the existing team feel like they can vouch for this new

work, and/or are willing to adapt their team scope to include it ? Having

two different groups under a single team and PTL only creates extra

governance problems. So if the teams working on it are distinct enough,

then the new project should probably be filed separately.

Another question you may ask yourself is whether alternate implementations

of the same functionality are OK. Is competition allowed between official

projects ? On one hand competition means dilution of effort, so you want

to minimize it. On the other you don't want to close evolutionary paths,

so you need to let alternate solutions grow. The Technical Committee answer

to that is: alternate solutions are allowed, as long as they are not

gratuitously competing. Competition must be between two different

technical approaches, not two different organizations or egos. Cooperation

must be considered first. This is all the more important the deeper you go

in the stack: it is obviously a lot easier to justify competition on an

OpenStack installer (which consumes all other projects), than on AuthN/AuthZ

(which all other projects rely on).

How ?

Let's do this ! How to proceed ? The first and hardest part is to pick a

name. We want to avoid having to rename the project later due to trademark

infringement, once it has built some name recognition. A good rule of thumb

is that if the name sounds good, it's probably already used somewhere.

Obscure made-up names, or word combinations are less likely to be a registered

trademark than dictionary words (or person names). Online searches can help

weeding out the worst candidates. Please be good citizens and also avoid

collision with other open source project names, even if they are not

trademarked.

Step 2, you need to create the project on OpenStack infrastructure. See the

Infra manual

for instructions, and reach out on the #openstack-infra IRC channel if you

need help.

The final step is to propose a change to the

openstack/governance

repository, to add your project team to the

reference/projects.yaml

file. That will serve as the official request to the Technical Committee,

so be sure to include a very informative commit message detailing how well

you fill the

new projects requirements.

Good examples of that would be

this change

or this one.

When ?

The timing of the request is important. In order to be able to assess

whether the new team behaves like the rest of the OpenStack community,

the Technical Committee usually requires that the new team operates on

OpenStack infrastructure (and collaborates on IRC and the mailing-list)

for a few months.

We also tend to freeze new team applications during the second part of

the development cycles, as we start preparing for the release and the PTG.

So the optimal timing would be to set up your project on OpenStack

infrastructure around the middle of one cycle, and propose for official

inclusion at the start of the next cycle (before the first development

milestone). Release schedules are published

here.

That's it !

I hope this article will help you avoid the most obvious traps

in your way to become an official OpenStack project. Feel free to reach out

to me (or any other

Technical Committee member)

if you have questions or would like extra advice !

On several occasions over the last months, I heard people exposing truths

about the OpenStack Technical Committee. However, those positions were often

inaccurate or incomplete. Arguably we are not communicating enough: governance

changes and resolutions that are brought to the TC are just approved or

rejected. That binary answer is generally not the whole story, and with only

the headline, it is easy to read too much in a past decision. We should do a

better job at communicating beyond that simple answer when the topic is more

complex, and at continuously explaining the role and limits of the TC.

Hopefully this blogpost will help, by busting some of those myths.

Myth #1: "the TC doesn't want Go in OpenStack"

This one comes from the recent rejection of a resolution proposing to add

golang to the list of approved languages, to support merging the hummingbird

feature branch into Swift's master branch. A more accurate way to present

that decision would be to say that a (short) majority of the TC members was not

supporting the addition of golang at that time and under the proposed

conditions. In summary it was more of a "not now, not this way" than a "never".

There were a number of reasons for this decision, but the crux was: adding a

language creates fragmentation and a support cost for all of the OpenStack

community, so we need to make sure "OpenStack" as a whole is successful with

it, beyond any specific project. That means for example having a clear plan

for integrating Go within all our standing processes, while trying to prevent

duplication of effort or gratuitous rewrites. The discussion was actually

recently restarted by Flavio in

this change. We'll need

resources to make this a success, so if you care, please jump in to help.

Myth #2: "the TC doesn't like competition with existing projects"

I'm not exactly sure where this one comes from. I can't think of any specific

TC decision that would explain it. Historically, back when we had programs,

a given team would own a given problem space and could essentially lock

alternatives out. But the Big Tent project structure reform changed that,

allowing competition to happen within our community.

Yes, we still want to encourage cooperation wherever it's possible, so we

still have a requirement which says "where it makes sense, the project

cooperates with existing projects rather than gratuitously competing or

reinventing the wheel". But as long as the new project is different or

presents a different value proposal, it should be fair game. For example we

accepted the Monasca team in the same problem space as the Telemetry team.

And we have several teams working on various deployment recipes.

That said, having competitive solutions in OpenStack on key problem spaces

(like base compute or networking services) creates interesting second-order

questions in terms of what is "core", trademark usage and interoperability.

Those are arguably more downstream concerns than upstream concerns, but that

explains why the deeper you go, the more difficult the community discussion

is likely to be.

Myth #3: "the TC does not set any direction"

There are multiple variants on that one, from "OpenStack needs a benevolent

dictator" to "a camel is a horse designed by a committee". The idea behind it

is that the TC needs to have a very opinionated plan for OpenStack and somehow

force everyone in our community to follow it. Part of this myth is trying to

apply single-vendor software development theory to an open collaboration, and

misunderstanding how other large open source projects (like the Linux kernel)

work.

While the TC members are all well-respected in our community, we can't

unilaterally decide everything for 2500+ developers from 300+ different

organizations, and expect them all to execute The Plan. What the TC can do,

however, is to define the mission, provide an environment, set principles,

enforce common practices, and arbitrate conflicts. In painting terms, the TC

provides the frame, the subject of the painting, a color palette and the

techniques that can be used. But it doesn't paint. Painting is done at each

project team level.

In this cycle, the TC started to drive some simple cross-community goals. The

idea is to collectively make visible progress on a given topic over the course

of a release cycle, to pay back technical debt or to implement a simple feature

across all of OpenStack projects. But this is done as a goal the community

agrees to work on, rather than a top-down mandate.

Myth #4: "the TC, due to the Big Tent, prevents proper focus"

This one is interesting, and I think its roots lie in some misunderstanding of

open source community dynamics. If you consider a finite set of resources and

a zero-sum-game community, then of course adding more projects results in less

resources being dedicated to "important projects". But an open community like

OpenStack is not a finite set of resources. The people and the organizations

in the OpenStack community work and cooperate on a number of projects. Before

the big tent, some of those would not be considered part of the OpenStack

projects, despite helping with the OpenStack mission and following the

OpenStack development principles, and therefore essentially being developed

by the OpenStack community.

Considering more (or less) projects as being part of our community doesn't

decrease (or increase) focus on "important projects". It's up to each

organization in OpenStack to focus on the set of projects it considers

important. For more on that, go read Ed Leafe's

brilliant blogpost, he expressed

it better than I can. Of course there are some efforts (like packaging)

where adding more projects results in diluting focus. But with every added

project comes new blood in our community (rather than artificially keeping it

out), and some of that new blood ends up helping on those efforts. It's not

a zero-sum game, and the big tent makes sure we are open to new ways of

achieving the OpenStack mission and have an inclusive and welcoming community.

This week we are renewing 6 seats

in the 13-member OpenStack Technical Committee. This election has attracted

a large number of candidates, which is a great sign that people care about

the Technical Committee. At the same time, there is a lot of misconceptions

in our community about what the TC is for, what it can or cannot do, and the

overlap with other groups. I'll try to clarify that in this post.

A misleading name

Part of the reason why there are so many misconceptions about the role of the

TC is that its name is pretty misleading. The Technical Committee is not

primarily technical: most of the issues that the TC tackles are open source

project governance issues. The TC is not really a committee either: it is a

group of elected people who will vote on resolutions and changes that are

proposed and which affect OpenStack as a whole. In the US, it is closer to

the Supreme Court than to anything else.

The primary role of the TC is to act as the final decision stage when it comes

to decision-making in the OpenStack open source project. It is extremely

important in an open source project to have a "bucket stops here" body that is

empowered to make decisions for the project if consensus and agreement cannot

be reached elsewhere -- otherwise it risks complete stand-still. I have been

involved in projects which were stuck in such governance grey area, and it

is a pretty ugly situation. It's interesting to note that the mere existence

of the final decision-making body is enough to achieve consensus at the lower

levels: two teams will prefer to find agreement between themselves rather

than call for final arbitration by the TC. This is a feature, not a bug.

An evolving mission

The mission of the TC is to lead the development of "OpenStack". As OpenStack

evolved into one framework with a lot of collaborating components, each of

which developed by project teams with their own governance, the mission of

the TC also evolved. Those days we focus on the "OpenStack" experience. What

does it mean to be an OpenStack project ? What does it imply in terms of

development practices, general principles, common goals, cooperation, minimal

QA or user experience ? Is this new group applying to become an official

OpenStack project team following enough of those rules to be considered "one

of us" ?

Some people would like the TC to single-handedly solve upgrades, scalability,

interoperability or end user experience. Some other people would like the

TC to let the individual project teams do as they want. Reality is, neither

of those extremes are likely to happen. The TC is just 13 (usually busy)

people, they can't solve all the issues in OpenStack by themselves. They are

elected because we trust them to make the right decisions for OpenStack, not

because they are the ultimate 100x engineers who can fix everything. On the

other hand, the TC is not powerless: by continuously refining what it means to

be an "OpenStack project", it can influence OpenStack project teams to address

the right topics. We did that through assert tags, which encouraged teams to

improve their upgrade story or adopt a sane feature deprecation policy. We'll

do that through release cycle goals, to drive visible improvements across

all the components in OpenStack.

Help, please

This is also why the TC needs all the help it can get. I'm excited we now have

the Architecture workgroup,

an open group of people interested in addressing long-standing architecture

issues in OpenStack as a whole. I'm thrilled that we have a

Stewardship workgroup,

an open group of people encouraging leaders in OpenStack to adopt Servant

Leadership practices and tools. We are electing 13 members to vote and make

the final calls, but all the ideas don't have to come from those 13 members.

If you're a candidate and you're not elected, it doesn't prevent you from

working on governance problems and propose changes.

So... If you are an eligible voter, please take the time to read the candidates

platform emails and vote. Whoever gets elected, they will need the legitimacy

that only a good turnout in elections can give them. And if you are a candidate

and don't get elected, please consider joining those open workgroups, and

propose governance changes -- keeping "OpenStack" together is definitely not

a 13-people task.

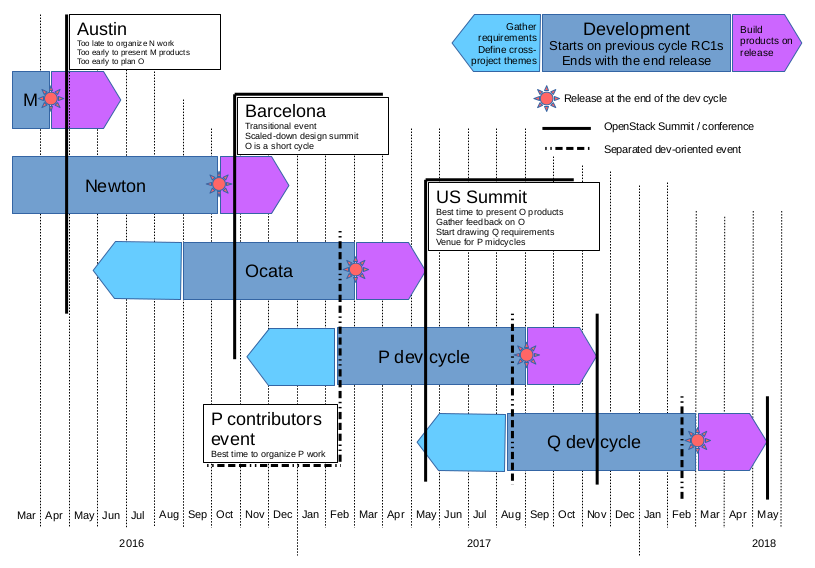

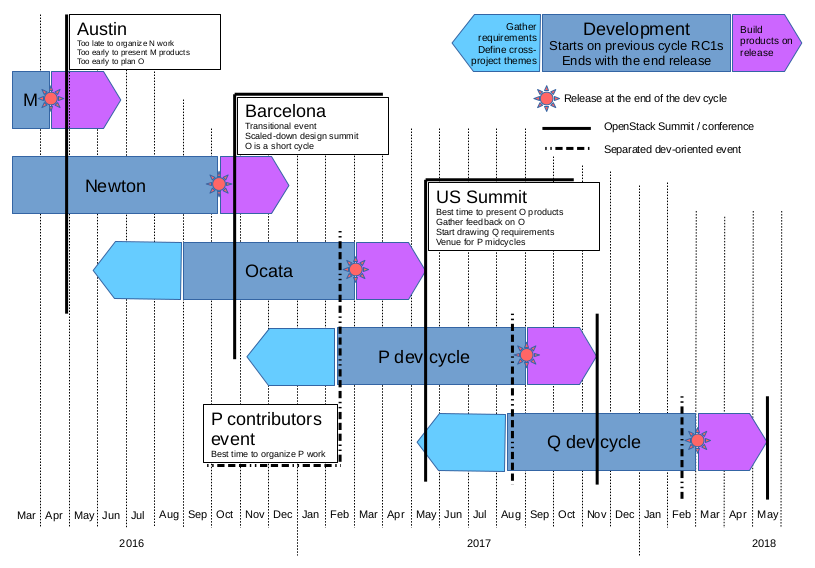

I was recently privately asked how I expected the split of the current

OpenStack Design Summit into two different events to enhance the overall

OpenStack development process. Here is the answer I gave...

We are working on splitting the "Design Summit" into a more open

requirements-gathering and feedback forum at the Summit on one side,

and a separated event for project team members on the other side. I expect

this change will greatly enhance the development process, for the following

reasons:

-

Key upstream developers and PTLs were too busy during the Summit week

to actually watch and listen. Having them more available during the Summit

week (where all of our community is present) should help a lot in getting

the right priorities across. The feedback sessions were also not very well

balanced (being organized as part of the upstream developer-centric event

called the "Design Summit"). Making it more like a regular Summit event will

help make it a neutral exchange forum between community peers (rather than

dev kings listening to grievances in their throne hall).

-

Project teams were lacking time to work together as a team: building

trust, organizing the work, agreeing on priorities and assigning tasks. The

current "Design Summit" doesn't work so well for that because it doubles as

a general forum and a lot of people outside the team members were attending

the sessions. There were also too many distractions to hang out between team

members and build social bonds. This is why a lot of teams organized specific,

separated events (the "midcycles"): to get more time together. The new

"Project Teams Gathering" event is all about providing that time to work

together as a team.

-

Partly as a result of separate midcycle events, project teams operated in

silos and were unlikely to be exposed or take on critical cross-project work.

They would also skip the cross-project workshops at the Design Summit since so

much is happening at the same time. The new event should provide specific time

for cross-project work, without anything running against it. It should

encourage team members from a vertical team (Nova, Neutron...) to join and

participate in horizontal / cross-project efforts (QA, Infra, technology

convergence, release theme...), to break out of their silo and become true

"OpenStack" contributors.

-

The timing of the "Design Summit" event was inefficient. It was too late

to organize work, too early to get feedback on the recent release. By splitting

the events, we put the main Summit further away from the release -- giving time

for packagers, deployers, solutions builders to build a product and start

experimenting with the new release. The quality of the feedback we get should

therefore improve a lot. It also lets us put the new event closer to the start

of the development cycle (closer to the previous cycle feature freeze),

ensuring there is less "down" time between cycles (almost two months in the

current setup).

So, in summary, I expect the new split event format to solve long-standing

issues that made the "Design Summit" no longer efficient. It should increase

our productivity, but also greatly improve the feedback loops between

downstream and upstream.

In a global and virtual community, high-bandwidth face-to-face time is

essential. This is why we made the OpenStack Design Summits an integral

part of our processes from day 0. Those were set at the beginning of each

of our development cycles to help set goals and organize the work for the

upcoming 6 months. At the same time and in the same location, a more

traditional conference was happening, ensuring a lot of interaction between

the upstream (producers) and downstream (consumers) parts of our community.

This setup, however, has a number of issues. For developers first: the

"conference" part of the common event got bigger and bigger and it is

difficult to focus on upstream work (and socially bond with your teammates)

with so much other commitments and distractions. The result is that our

design summits are a lot less productive than they used to be, and we

organize other events ("midcycles") to fill our focus and small-group

socialization needs. The timing of the event (a couple of weeks after the

previous cycle release) is also suboptimal: it is way too late to gather any

sort of requirements and priorities for the already-started new cycle, and

also too late to do any sort of work planning (the cycle work started almost

2 months ago).

But it's not just suboptimal for developers. For contributing companies,

flying all their developers to expensive cities and conference hotels so

that they can attend the Design Summit is pretty costly, and the goals of

the summit location (reaching out to users everywhere) do not necessarily

align with the goals of the Design Summit location (minimize and balance

travel costs for existing contributors). For the companies that build products

and distributions on top of the recent release, the timing of the common event

is not so great either: it is difficult to show off products based on the

recent release only two weeks after it's out. The summit date is also too

early to leverage all the users attending the summit to gather feedback on

the recent release -- not a lot of people would have tried upgrades by

summit time. Finally a common event is also suboptimal for the events

organization : finding venues that can accommodate both events is becoming

increasingly complicated.

Time is ripe for a change. After Tokyo, we at the Foundation have been

considering options on how to evolve our events to solve those issues. This

proposal is the result of this work. There is no perfect solution here (and

this is still work in progress), but we are confident that this strawman

solution solves a lot more problems than it creates, and balances the needs

of the various constituents of our community.

The idea would be to split the events. The first event would be for upstream

technical contributors to OpenStack. It would be held in a simpler, scaled-back

setting that would let all OpenStack project teams meet in separate rooms,

but in a co-located event that would make it easy to have ad-hoc cross-project

discussions. It would happen closer to the centers of mass of contributors,

in less-expensive locations.

More importantly, it would be set to happen a couple of weeks before the

previous cycle release. There is a lot of overlap between cycles. Work on a

cycle starts at the previous cycle feature freeze, while there is still 5

weeks to go. Most people switch full-time to the next cycle by RC1.

Organizing the event just after that time lets us organize the work and

kickstart the new cycle at the best moment. It also allows us to use our time

together to quickly address last-minute release-critical issues if such

issues arise.

The second event would be the main downstream business conference, with

high-end keynotes, marketplace and breakout sessions. It would be organized

two or three months after the release, to give time for all downstream

users to deploy and build products on top of the release. It would be the best

time to gather feedback on the recent release, and also the best time to have

strategic discussions: start gathering requirements for the next cycle,

leveraging the very large cross-section of all our community that attends

the event.

To that effect, we'd still hold a number of strategic planning sessions at

the main event to gather feedback, determine requirements and define overall

cross-project themes, but the session format would not require all project

contributors to attend. A subset of contributors who would like to participate

in these sessions can collect and relay feedback to other team members for

implementation (similar to the Ops midcycle). Other contributors will also

want to get more involved in the conference, whether that's giving

presentations or hearing user stories.

The split should ideally reduce the needs to organize separate in-person

mid-cycle events. If some are still needed, the main conference venue and

time could easily be used to provide space for such midcycle events (given

that it would end up happening in the middle of the cycle).

In practice, the split means that we need to stagger the events and cycles.

We have a long time between Barcelona and the Q1 Summit in the US, so the

idea would be to use that long period to insert a smaller cycle (Ocata) with

a release early March, 2017 and have the first specific contributors event

at the start of the P cycle, mid-February, 2017. With the already-planned

events in 2016 and 2017 it is the earliest we can make the transition. We'd

have a last, scaled-down design summit in Barcelona to plan the shorter cycle.

With that setup, we hope that we can restore the productivity and focus of

the face-to-face contributors gathering, reduce the need to have midcycle

events for social bonding and team building, keep the cost of getting all

contributors together once per cycle under control, maintain the feedback

loops with all the constituents of the OpenStack community at the main event,

and better align the timing of each event with the reality of the release

cycles.

NB: You will note that I did not name the separated event "Design Summit" --

that is because Design will now be split into feedback/requirements

gathering (the why at the main event) and execution planning and

kickstarting (the how at the contributors-oriented event), so that name

doesn't feel right anymore. We can bikeshed on the name for the new event

later :)

This was also posted to the openstack-dev ML:

please comment and follow-up there if you have thoughts to share.